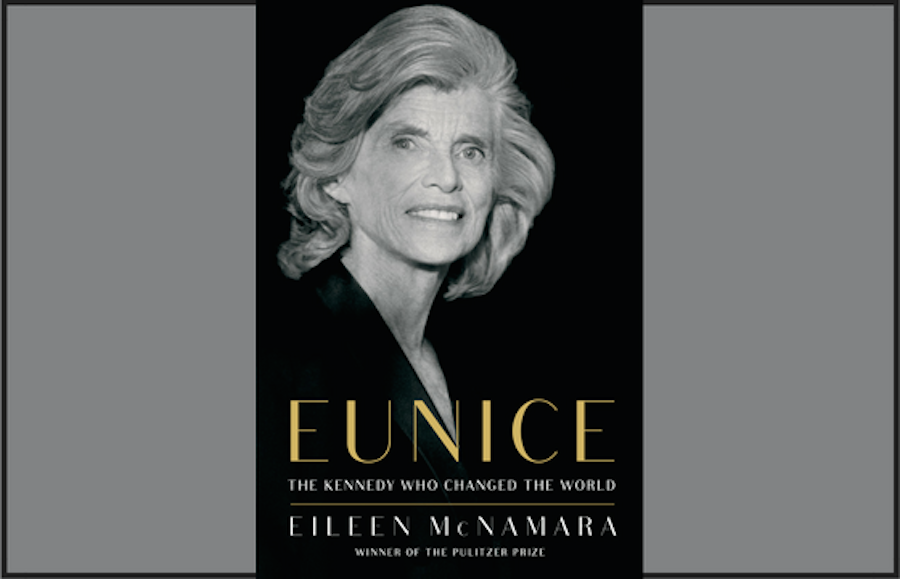

I’ve Been Thinking … Eunice Kennedy Shriver: The Kennedy Who Changed the World

In her cobalt-blue wool suit and white kidskin gloves she could have been mistaken for a guest at a White House social reception instead of the architect of the pioneering legislation the president of the United States was about to sign.

As John F. Kennedy slid into his leather armchair at the center of the conference table in the Cabinet Room, the forty-two-year-old suburban mother of three receded behind a wall of dignitaries, including the Speaker of the House, the Senate majority leader, the secretary of labor, the chief of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins Hospital and assorted senators and congressmen.

She does not appear in the formal group portraits from that day, having settled into a spot far behind the president against the east wall, nearly enfolded by the green brocade drapes bracketing the French doors that open onto the Rose Garden. President Kennedy does not mention her in his recorded remarks at the signing ceremony for the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act of 1963, singling out instead Senator Lister Hill, of Alabama, chairman of the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, and Representative Oren Harris, of Arkansas, chairman of the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, who shepherded S. 1576 to passage.

It was only after he had distributed all but one of the ceremonial fountain pens that the president turned to look for Eunice Kennedy Shriver and, rising from his seat, strode through the crowd toward the back wall to hand the last pen to his sister, the guiding force behind an unprecedented federal commitment to combating what we then called mental retardation.

“This bill will expand our knowledge, provide research facilities to determine the cause of retardation, establish university related diagnostic research clinics and permit the construction of university centers for the care of the retarded,” the president told those gathered. “For the first time, parents and children will have available comprehensive facilities to diagnose and either cure or treat mental retardation. For the first time, there will be research centers capable of putting together teams of experts working in many different fields. For the first time, state and federal governments and voluntary organizations will be able to coordinate their manpower and facilities in a single effort to cure and treat this condition.”

There had been no reason to expect that Kennedy would make this issue a White House priority. Foreign policy was his primary focus in 1963, a year in which he declared to the people of the divided city of Berlin that “in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is ‘Ich bin ein Berliner,’” a year in which he would commit 16,000 U.S. troops to South Vietnam and covert energy toward ousting Fidel Castro from Cuba. Civil rights was the most pressing item on his domestic agenda the year that Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace blocked the entrance of three black students into the University of Alabama, the year that a white supremacist murdered Mississippi NAACP field director Medgar Evers, the year that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have A Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington.

Kennedy’s indifference had long frustrated advocates for those with intellectual disabilities. The memory still stung of then-Senator Kennedy brushing past Elizabeth M. Boggs, the president of the National Association for Retarded Children, in a Capitol Hill corridor where she was waiting to testify before the Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare on the urgent need for special education services. Kennedy was a member of that committee but he did not stick around that April day in 1957 for the hearing even though Boggs knew – as the nation as yet did not – that Kennedy’s oldest sister Rosemary was institutionalized in Wisconsin after a prefrontal lobotomy, undertaken in a misguided attempt to cure the mental illness that compounded her intellectual disabilities, had left her incapacitated.

But Boggs and her cause would find a fierce ally elsewhere in the Kennedy clan. Eunice Kennedy Shriver took the reins of the Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. Foundation – named for her oldest brother, killed in combat in World War II – around the time Jack blew past Boggs in that hallway. Eunice turned the attention of the family’s previously unfocused charity exclusively to the needs of those with intellectual disabilities. With her father’s fortune and her husband’s help, she traveled the country, consulting experts and educating herself about the scope of the problem and the dearth of resources devoted to addressing it. Her efforts culminated in millions of dollars in grants from the Kennedy Foundation to researchers at Harvard, Johns Hopkins, Georgetown, Chicago, Wisconsin and Stanford.

It was only a beginning. She had learned enough by the time her oldest surviving brother was elected president, on November 8, 1960, to know that the efforts of a small family foundation were no match for what the federal government could, and in her view should, be doing for the 5.4 million children and adults in the United States with intellectual disabilities. The few federal programs that did exist were scattered throughout the bureaucracy, intermingled with aid for the physically handicapped and geared toward adults. It was not nearly enough.

Her brother’s election gave her an opportunity to do more. Before he had even taken the oath of office, Eunice secured from Jack a commitment to appoint a presidential panel to investigate the needs and to propose federal legislation to meet them. The president gave her a free hand and she seeded the 27-member President’s Panel on Mental Retardation with the most knowledgeable people in the field, including Boggs, a chemist by training and herself the mother of a son with profound disabilities.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver herself was not a member of the President’s Panel; she said she did not want charges of nepotism to overshadow the work, a concern not shared by her younger brothers. Jack had appointed Bobby his attorney general and anointed Teddy as the senator-in-waiting from Massachusetts, where he had arranged for his Harvard roommate to warm his old seat until 1962 when Ted would be old enough to run.

Officially, Eunice was a behind-the-scene “consultant” to the group that she had willed into existence and drove to produce a report for the President within one year and legislation for him to sign within two. In reality, Eunice was the driving force, “like a spark plug,” according to Judge David L. Bazelon who sat on the panel as well as on the District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals. “There is no doubt that she sparked it and made it spark.”

She was also political strategist enough to know “that this work had to be Jack’s work if it was to be successful. The way to make things happen in Washington was for people to see this issue as important to Jack. It had to be an important issue, not a family issue. I never wanted people to think that what President Kennedy was doing was about Rosemary. Then they would have dismissed it as a personal matter. It wasn’t. It was about the outrageous neglect. It was about the outrage. I wanted all those experts to face the injustice of it all.”

She had pulled it off.

At the edge of that gathering of luminaries in the Cabinet Room on the last day of October in 1963, how moved she must have been to hear the president pledge the nation’s communal responsibility to those with intellectual disabilities, a commitment that was unimaginable only a few years before.

“It was said, in an earlier age, that the mind of man is a far country which can be neither approached nor explored. But today, under present conditions of scientific achievement, it will be possible for a nation as rich in human and material resources as ours to make the most remote recesses of the mind accessible,” the President vowed. “The mentally ill and the mentally retarded need no longer be alien to our affections or beyond the help of our communities.”

It was the last bill John Fitzgerald Kennedy would ever sign. No one in the Cabinet Room on that sunny Thursday morning could have imagined that three weeks later an assassin’s bullet in Dallas would end the life of the 35th president of the United States.

As much as John F. Kennedy’s death would traumatize the nation he led, it would upend the dynamics in the family he left behind. There would be no more wall-hugging for Eunice Kennedy Shriver. Without her brother in the White House, she would have to come out from behind the curtains to lead the movement she had just put on the national agenda.

From EUNICE by Eileen McNamara. Copyright © 2018 by Eileen McNamara. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

READ MORE STORIES THAT MOVE HUMANITY FORWARD

READ MORE STORIES THAT MOVE HUMANITY FORWARD

SIGN UP FOR MARIA’S SUNDAY PAPER