I was about thirty when I first felt drawn to the contemplative life. Inspired by reading Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk, I had visions of joining a monastic community. I thought the Abbey of Gethsemani, where Merton spent half his life, would be just right. Compared to Washington, DC—where I was caught up in the frenzy of my work as a community organizer—life at Gethsemani amid the wooded hills of Kentucky sounded idyllic.

Unfortunately, there were several major obstacles between monkhood and me. I was married, the father of

three children; had a job on which my family depended; and was considerably more Quaker than Catholic. Clearly, my “visions” of a monastic life were hallucinations. So instead of applying to become a novice at Gethsemani, I ordered one of the abbey’s famous fruitcakes, which are soaked and aged in fine Kentucky bourbon.

Fortified with fruitcake, I went in search of some way to live as a contemplative amid the world’s madness. Over the next few years, I read about the mystical stream that runs through all of the world’s wisdom traditions. I attended guided retreats and experimented with several popular contemplative practices. But, with the exception of the Quaker meeting for worship, I couldn’t find a practice

compatible with my temperament, religious inclinations, and life situation.

Necessity being the mother of invention, it struck me that contemplation didn’t depend on a particular practice. All forms of contemplation share the same goal: to help us see through the deceptions of self and world in order to get in touch with what Howard Thurman called “the sound of the genuine” within us and around us. Contemplation does not need to be defined in terms of particular practices,

such as meditation, yoga, tai chi, or lectio divina. Instead, it can be defined by its function: contemplation is any way one has of penetrating illusion and touching reality.

That definition opened my eyes to myriad ways I might lead a contemplative life—as long as I keep trying to turn experience into insight. For example, facing into failure can help vaporize the illusions that keep me from seeing reality. When I succeed at something, I don’t spend much time wondering what I might learn from it. Instead, I congratulate myself on how clever I am, fortifying one of my favorite illusions in the process.

But when failure bursts my ego-balloon, I spend long hours trying to understand what went wrong, often learning (or relearning) that the “what” is within me. Failure gives me a chance to touch hard truths about myself and my relation to the world that I evade when I’m basking in the glow of success and the illusions it breeds. Failure is one of the many forms contemplation can take.

Life is full of challenges that can turn us into contemplatives. Years ago, I met Maureen, a single mother with a daughter named Rebecca who had severe developmental disabilities and could do very little for herself. So Maureen had to live two lives, leaving her with neither time nor energy to go on retreat or take up formal spiritual practices. And yet Maureen was a world-class contemplative.

In her love for Rebecca—who would never be “successful” or “useful” or “beautiful” by conventional standards—Maureen had penetrated every cruel illusion our culture harbors about what makes a human being worthy. She had touched the reality that Rebecca was of profound value in and of herself, a being precious to the earth and a cherished child of God, as everyone is.

To be in Maureen’s presence was to feel yourself held in a contemplative circle of grace. When you are with someone who values you not for what you do but for who you are, there’s no need to pretend or wear a mask. You experience the blessed relief that comes from needing to be nothing other than your unguarded and unvarnished self.

Even the most devastating experience can be a doorway to contemplation. At least, that’s been true for me in the wake of my depressions. While you are down there, reality disappears. Everything is illusion foisted on you by the self-destructive “voice of depression,” the voice that keeps telling you you are a waste of space, the world is a torture chamber, and nothing short of death can give you peace. But as you emerge, problems become manageable again,and everyday realities—a crimson glow on the horizon, a

friend’s love, a stranger’s kindness, another precious day of life—present themselves as the treasures they truly are.

If contemplation is about penetrating illusion and touching reality, why do we commiserate with others when they tell us about an experience that’s “disillusioned” them? “Oh, I’m so sorry,” we’ll say. “Please, let me comfort you.” Surely it would be better to say, “Congratulations! You’ve lost another illusion, which takes you a step closer to the solid ground of reality. Please, let me help disillusion you even further.”

I envy people who have whatever it takes to practice classic contemplative disciplines day in and day out—practices that help them get beyond the smoke and mirrors and see the truth about themselves and the world. I call these people “contemplatives by intention,” and some I’ve known seem to be able to get ahead of the train wreck. But I’m not a member of that blessed band.

I’m a “contemplative by catastrophe.” My wake-up calls generally come after the wreck has happened and I’m trying to dig my way out of the debris. I do not recommend this path as a conscious choice. But if you, dear reader, have a story similar to mine, I come as the bearer of glad tidings. Catastrophe, too, can be a contemplative path, pitched and perilous as it may be.

I’m still on that path, and daily I stay alert for the disillusionment that will reveal the next thing I need to know about myself and/or the world. Life can always be counted on to send something my way—who knows what it will be today? Maybe a reminder of a part of my past that I regret. Maybe a spot on critique of something I thought I’d done well. Maybe a fresh political outrage that makes me feel that my country has lost all semblance of soul.

Whatever it is, I’ll try to work my way through it until a hopeful reality is revealed on the other side. Regret can be turned into blessing. Criticism can refocus our work or strengthen our resolve. When we feel certain that the human soul is no longer at work in the world, it’s time to make sure that ours is visible to someone, somewhere. Those are some of the fruits that can come from being a

contemplative by catastrophe.

And never forget that a few slices of bourbon-soaked Trappist fruitcake can help contemplation along.

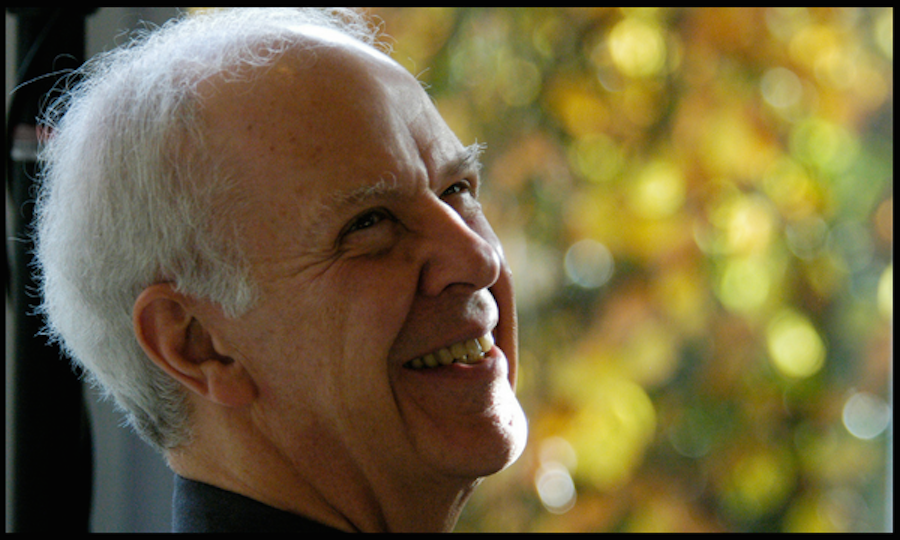

Excerpted from “On the Brink of Everything: Grace, Gravity & Getting Old” by Parker J. Palmer Copyright © 2018 by Parker J. Palmer. Printed with permission from Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2018, www.bkconnection.com

This essay was featured in the July 29th edition of The Sunday Paper, Maria Shriver’s free weekly newsletter for people with passion and purpose. To get inspiring and informative content like this piece delivered straight to your inbox each Sunday morning, click here to subscribe.