Depolarizing Our Divided Discussions

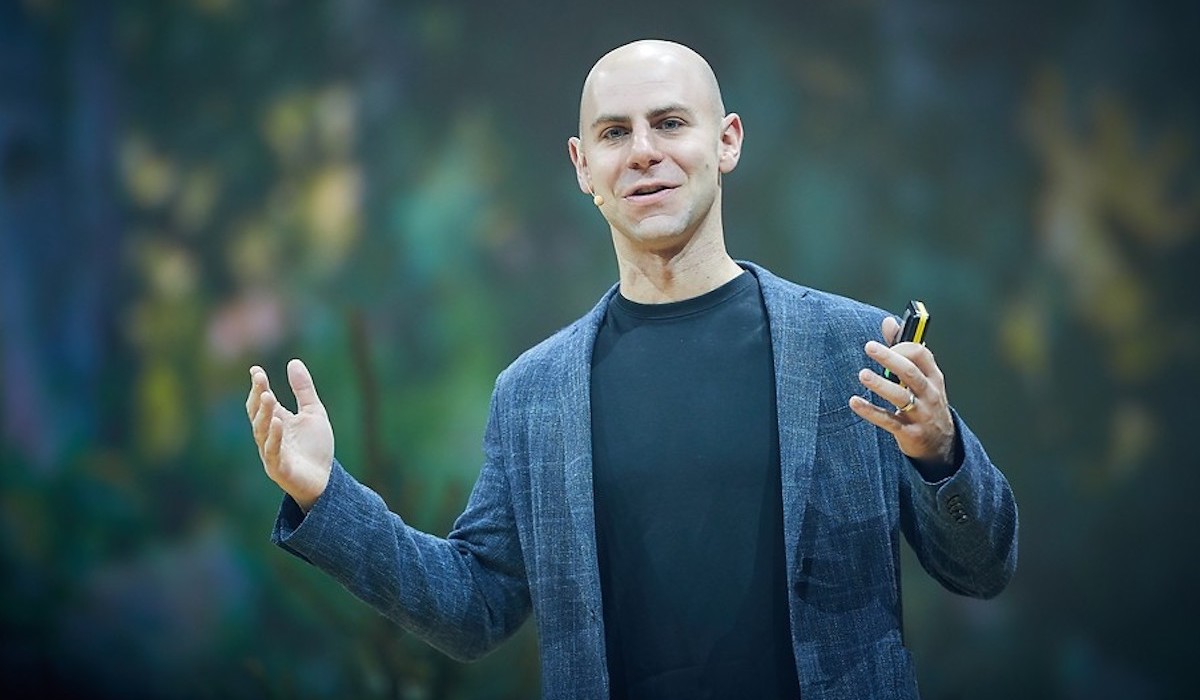

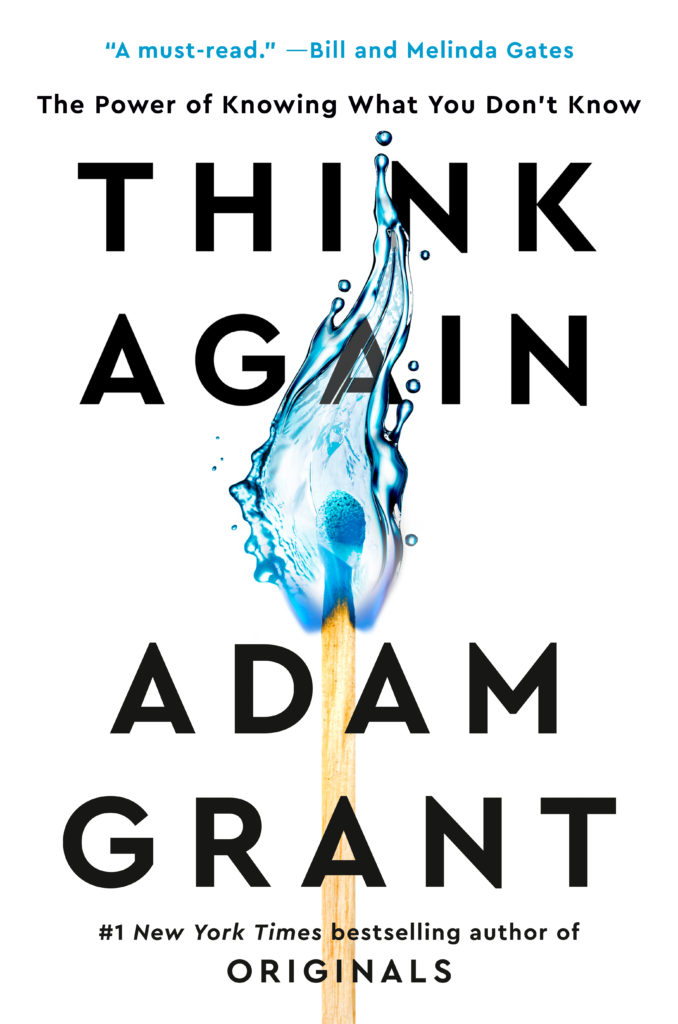

Below is an excerpt from Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know by Adam Grant

Eager to have a jaw-clenching, emotionally fraught argument about abortion? If you think you can handle it, head for the second floor of a brick building on the Columbia University campus in New York. It’s the home of the Difficult Conversations Lab.

If you’re brave enough to visit, you’ll be matched up with a stranger who strongly disagrees with your views on a controversial topic. You’ll be given just 20 minutes to discuss the issue, and then you’ll both have to decide whether you’ve aligned enough to write and sign a joint statement on your shared views around abortion laws. If you’re able to do so—no small feat—your statement will be posted on a public forum.

To put you in the right mindset before you begin your conversation about abortion, you and a stranger read a news article about another divisive issue: gun control. What you don’t know is that there are different versions of the gun control article, and which one you read is going to have a major impact on whether you land on the same page about abortion.

If the gun control article covers both sides of the issue, making a balanced case for both gun rights and gun legislation, you and your adversary have a decent chance at reaching consensus on abortion. In one experiment, after reading a “both-sides” article, 46 percent of pairs were able to find enough common ground to draft and sign a statement together. That’s a remarkable result.

But something far more impressive happened. Some pairs had been randomly assigned to read another version of the gun control article, which led 100 percent of them to generate and sign a joint statement about abortion laws.

That version of the article featured the same information but presented it differently. Instead of describing gun control as a black-and-white disagreement between two sides, the article framed the debate as a complex issue with many shades of grey, representing a number of different viewpoints.

Where charged issues are concerned, it’s not enough simply to see the opinions of the other side. Hearing an opposing view doesn’t necessarily motivate you to rethink your own stance; it makes it easier for you to stick to your guns (or your gun bans). Presenting two extremes isn’t the solution; it’s part of the polarization problem.

Psychologists have a name for this: binary bias. It’s a basic human tendency to seek clarity and closure by simplifying a complex continuum into two categories. To paraphrase the humorist Robert Benchley, there are two kinds of people: those who divide the world into two kinds of people, and those who don’t.

An antidote is complexifying: showcasing the range of perspectives on a given topic. When media headlines proclaim a divided America on gun laws, they’re missing a lot of complexity. Yes, there’s a gap of 47-50 percentage points between Republicans and Democrats on support for banning and buying back assault weapons. Yet polls show bipartisan consensus on required background checks (supported by 83 percent of Republicans and 96 percent of Democrats) and mental health screenings (favored by 81 percent of Republicans and 94 percent of Democrats).

A dose of complexity can lead us to rethink our opinions. If people read the binary version of the gun control article, they defended their own perspective more often than they showed an interest in their opponent’s. If they read the complexified version, they made about twice as many comments about common ground as about their own views. They asserted fewer opinions and asked more questions. At the end of the conversation, they generated more sophisticated, higher-quality position statements—and both parties came away more satisfied.

We might believe we’re making progress by discussing hot-button issues as two sides of a coin, but people are actually more inclined to think again if we present these topics through the many lenses of a prism. To borrow a phrase from Walt Whitman, it takes a multitude of views to help people realize that they too contain multitudes.

From Think Again by Adam Grant, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (c) 2021 by Adam Grant.

This excerpt was featured in the February 7, 2021 edition of The Sunday Paper. The Sunday Paper publishes News and Views that Rise Above the Noise and Inspires Hearts and Minds. To get The Sunday Paper delivered to your inbox each Sunday morning for free, click here to subscribe.