The following is an excerpt from “Barking to the Choir: The Power of Radical Kinship” by Father Gregory Boyle, founder of Homeboy Industries.

Start with a title.

It’s a terrible way to write a book.

So I’m in my office at Homeboy Industries talking with Ramón, a gang member who works in our bakery.

Lately, he has been veering into the lane of oncoming traffic. He’s late for work, sometimes missing it entirely, and his supervisors tell me he is in need of an emergency “attitude-ectomy.” I’m running it down to him, giving him “kletcha”—schooling him, grabbing hold of the steering wheel to correct his course. He waves me off and says, self-assuredly, “Don’t sweat it, bald-headed . . . You’re barking to the choir.”

Note to self: title of my next book.

I immediately liked, of course, the combo-burger nature of his phraseology. The marriage of “barking up the wrong tree” to “preaching to the choir.” It works. It calls for a rethinking of our status quo, no longer satisfied with the way the world is lulled into operating and yearning for a new vision. It is on the lookout for ways to confound and deconstruct.

What gets translated in Scripture from the Greek metanoia as “repent” means “to go beyond the mind we have.” And the “bark- ing” is directed at the “Choir”—those folks who “repent” and truly long for a different construct, a radically altered way of proceeding and who seek “a better God than the one we have.” The gospel can expose the game in which “the Choir” can find itself often compla- cently stuck. The game that keeps us from the kinship for which we long—the endless judging, competing, comparing, and terror that prevents us from turning the corner and bumping into that “something new.” That “something” is the entering the kinship of God . . . here and now, no longer satisfied with the “pie in the sky when we die.”

The Choir is everyone who longs of and aches to widen their “loving look” at what’s right in front of them. What the Choir is searching for is the authentic.

In a recent New Yorker profile of American Baptists, the congregation’s leadership resigned itself to the fact that “secular culture” would always be “hostile” to Christianity. I don’t believe this is true. Our culture is hostile only to the inauthentic living of the gospel. It sniffs out hypocrisy everywhere and knows when Christians aren’t taking seriously, what Jesus took seriously. It is, by and large, hostile to the right things. It actually longs to embrace the gospel of inclusion and nonviolence, of compassionate love and acceptance. Even atheists cherish such a prospect.

Human beings are settlers, but not in the pioneer sense. It is our human occupational hazard to settle for little. We settle for purity and piety when we are being invited to an exquisite holiness. We set- tle for the fear-driven when love longs to be our engine. We settle for a puny, vindictive God when we are being nudged always closer to this wildly inclusive, larger-than-any-life God. We allow our sense of God to atrophy. We settle for the illusion of separation when we are endlessly asked to enter into kinship with all. The Choir has set- tled for little . . . and the “barking,” like a protective sheepdog, wants to guide us back to the expansiveness of God’s own longing.

The Choir is certainly more than “the Church.” And in many ways, Homeboy Industries is called to be now, what the world is called to be ultimately. The Choir understands this. Homeboy wants to give rise not only to the idea of redemptive second chances but also to a new model of church as a community of inclusive kinship and tenderness. The Choir consists of those people who want to Occupy Everywhere, not just Wall Street, and seek, in the here and now, what the world is ultimately designed to become. The Choir, at the end of its living, hopes to give cause to those folks from the Westboro Baptist Church . . . to protest at their funeral.

The Choir aims to stand with the most vulnerable, directing their care to the widow, the orphan, the stranger, and the poor. Those in the Choir want to be taught at the feet of the least. And they want to be caught up in a new model that topples an old order, something wildly subversive and new.

Begin with a title and work backward.

It’s been more than thirty years since I first met Dolores Mission Church as pastor and ultimately came to watch Homeboy Indus- tries, born in that poor, prophetic community in 1988, evolve into the largest gang intervention, rehab, and reentry program on the planet. Homeboy has similarly helped 147 programs in the United States and 16 programs outside the country find their beginnings in what we call the Global Homeboy Network.

As in my previous book, Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion, the essays presented here, again, draw upon three decades of daily interaction with gang members as they jetti- son their gang past for lives more full in freedom, love, and a bright reimagining of a future for themselves.

I’ll try not to repeat myself.

I get invited to give lots of talks: workshops, keynote addresses, luncheon gigs. YouTube is the bane of my existence. I can go to, say, the University of Findlay in Ohio, or Calvin College in Grand Rapids—two places I’ve never been before—and there will be a handful of folks who’ve “heard that story before.” It happens. I was invited once to give the keynote at an annual gathering of Foster Grandparents in Southern California. I had spoken at the same event the summer before. Virtually the same people, and I’m not sure why they invited me back two summers in a row. After my talk, a grandmother approaches me. I think she liked the talk— there were big tears in her eyes. She grabs both my hands in hers and says, with great emotion, “I heard you last year.” She pauses to compose herself. “It never gets better.” I suppose I’m delusional in thinking she misspoke.

Anyway, I’ll try not to repeat myself.

I can’t think, breathe, or proceed—ever—without stories, par- ables, and wisdom gleaned from knowing these men and women who find their way into our headquarters on the outskirts of Chi- natown. We are in the heart of Los Angeles, representing the heart of Los Angeles, and always wanting to model and give a foretaste of the kinship that is God’s dream come true. Homeboy Industries doesn’t just want to join a dialogue—it wants to create it. It wants to keep its aim true, extol the holiness of second chances, and jostle our mind-sets when they settle for less. As a homie told me once, “At Homeboy, our brand has a heartbeat.”

In all my years of living, I have never been given greater access to the tenderness of God than through the channel of the thousands of homies I’ve been privileged to know. The day simply won’t ever come when I am nobler or more compassionate or asked to carry more than these men and women.

Jermaine came to see me, released after more than twenty years in prison. He is a sturdy African American gang member now in his mid-forties. His demeanor is gentle and so, so kind. As I’m speaking with him, I ask if he’s on parole and he says yes. Then I ask, “High control?” He nods affirmatively. “I hope you don’t mind me asking this: How did someone as kind and gentle and tender as you end up . . . on high-control parole?” Jermaine pauses, then says meekly, “Rough childhood?” Both his manner and words make us laugh. His mom was a prostitute and his father was killed when Jermaine, the oldest of three brothers, was nine. After his father’s funeral, his mother rented an apartment, deposited all the boys there, walked to the door, and closed it. They never saw her again. In the many months that followed, Jermaine would take his two younger siblings and sit on the stoop of neighbors’ porches. When the residents would inquire, he’d say simply: “We ain’t leavin’ till ya feed us.” We ended our conversation that day with him telling me: “I’ve decided to be loving and kind in the world. Now . . . just hopin’ . . . the world will return the favor.”

In the pages that follow are the lives of men and women who have pointed the way for me. For my part, to sit at their feet, has been nothing short of salvific.

I can’t write essays about things that matter to me without fill- ing them with God, Jesus, and the gospel rubbing shoulders with stories, snapshots, parables, and wisdom from “the barrio.” Also, there is here a regular infusion of “Ignatian spirituality”: being a son of Ignatius myself, all the stories of my life get filtered through this Jesuit lens. I only hope the vignettes, koans, and images won’t feel too cobbled, the connections too forced, in the stringing of all this together in my second book.

In these elongated homilies, I want to capture the homies’ voices as a window of truth to soften the images of them often por- trayed in TV and movies.

I should also say that, as in my last book, I don’t mention the name of any gang—they’ve been the cause of too much sadness— and I’ve changed all the names of the homies here. People had previously criticized the absence of a glossary and a reluctance to translate the Spanish. Again, here, I’m hopeful that the context and meaning will all become evident. There will be the occasion when I do translate something. I will, from time to time, step back and explain something. For instance, when gang members say “fool,” they don’t mean anything by it. It roughly means “guy.” “Did you see that fool that walked by?” Once Martin came in excited to tell me that he had just gotten hired at White Memorial Hospital.

“Congratulations. What do ya do there?” “I’m the main fool at the gift shop.”

“Wow . . . hey . . . let me know if there’s an opening for assistant fool.”

In the end, each chapter aspires to connect us to a larger view and to participate in a larger love.

I’ve learned from giving thousands of talks that you never ap- peal to the conscience of your audience but, rather, introduce them to their own goodness. I remember, in my earliest days, that I used to be so angry. In talks, in op-ed pieces, in radio interviews, I shook my fist a lot. My speeches would rail against indifference and how the young men and women I buried seemed to matter less in the world than other lives. I eventually learned that shaking one’s fist at something doesn’t change it. Only love gets fists to open. Only love leads to a conjuring of kinship within reach of the actual lives we live.

When Karen Toshima, a graphic artist on a date, was caught in gang crossfire in Westwood Village in 1988, police were pulled from other divisions in Los Angeles and pumped into this area ad- jacent to UCLA. Detectives were reassigned from other homicide investigations and directed to this case. A hefty reward was offered for information that would lead to the arrest and conviction of who- ever had done this. I would soon be burying eight kids in a three- week period in those early days. No cops were shuffled around, no detectives were reassigned, and certainly no rewards were offered to anyone for anything . . . leading me to think that one life lost in Westwood was worth more than hundreds in the barrio. I ranted and shook my fist a great deal. As of this writing, I have buried exactly 220 young human beings killed because of gang violence. In those early days, I would shake my fist a lot at this disparity.

I think Homeboy Industries has changed the metaphor in Los Angeles when it comes to gangs. It has invited the people who live here to recognize their own greatness and does not accuse them of anything. It beckons to their generosity and lauds them for being “smart on crime” instead of mindlessly tough. It seeks an invest- ment rather than futile and endless incarceration. Both this book and Homeboy Industries do not want to simply “point something out” but rather to try and point the way.

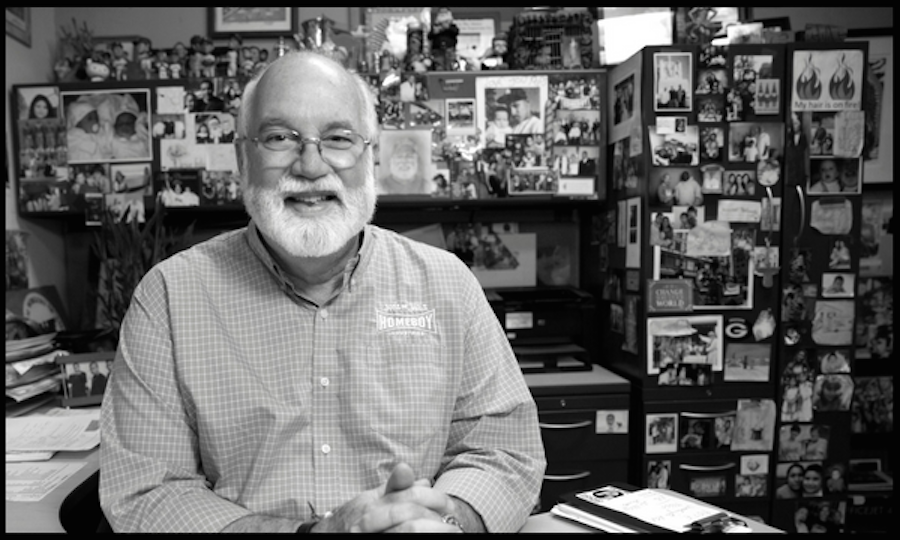

Gregory Boyle is a Jesuit priest and the founder of Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles, the largest gang-intervention, rehabilitation, and reentry program in the world. He has received the California Peace Prize and been inducted into the California Hall of Fame. In 2014, the White House named Boyle a Champion of Change. He received the University of Notre Dame’s 2017 Laetare Medal, the oldest honor given to American Catholics. He is the acclaimed author of “Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion” (2010). “Barking to the Choir” is his second book, and he will be donating all net proceeds to Homeboy Industries. You can learn more at HomeboyIndustries.org.

This essay was featured in the July 22nd edition of The Sunday Paper, Maria Shriver’s free weekly newsletter for people with passion and purpose. To get inspiring and informative content like this piece delivered straight to your inbox each Sunday morning, click here to subscribe.