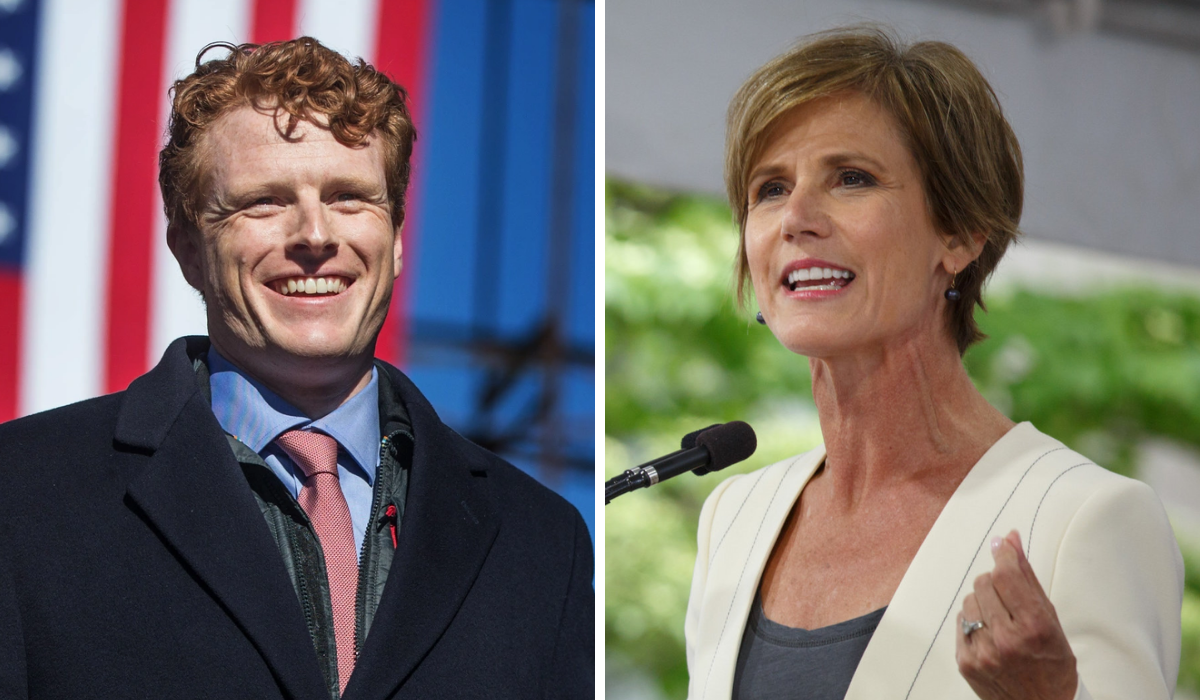

Joe Kennedy III and Sally Yates Talk Integrity in the Public Space

Recently, former US Congressman Joe Kennedy III sat down for a video chat with former United States Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates for an exclusive Sunday Paper Live discussion about integrity in politics. We invite you to join these two inspirational leaders in The Open Field.

A Conversation with Joe Kennedy III and Sally Yates

Joe: You spent nearly three decades at the Department of Justice. You served under both Democrat and Republican administrations. You were actually recommended by officials from both parties. You have earned the trust and respect of officials, including former members of Congress, as diverse as Congressman Trey Gowdy to Congressman Joe Kennedy. Sally, how do you earn and keep that respect in such partisan times as we are now, but also given the consequence and the heavyweight of the types of cases that you’re working on?

Sally Yates: Well, if the Department of Justice is doing its job the right way, it’s operating differently than other departments of the government. Yes, it’s part of the executive branch, but going back to that trust there. For the people of this country to trust, that the rule of law is being administered and the rule of law, when I say that I mean that the same rules apply to everybody. Nobody’s above the law, and we’re not using the power of the justice department to go after received (“perceived” perhaps?) enemies or political foes. For people to have confidence in that, it has to be administered in a partisan blind way. That doesn’t mean there aren’t changes in policies and an emphasis depending on the administration or the president, and that’s perfectly appropriate, but not individual decisions made in cases in a partisan way. And that was how I grew up in the justice department.

I prosecuted public corruption cases for the most part when I was a line prosecutor. And those are certainly fraught cases. As it turned out, most of the people, not all, but most of the folks that I ended up prosecuting were Democrats, not Republicans, because we prosecuted a lot of local corruption cases because the local DAs couldn’t really do them. And I found in our office, [it was never an … I mean,] I didn’t even know what the political affiliation was of most of my colleagues. When I was US attorney was hiring people, I didn’t know and didn’t care what their political affiliation was.

And so, I think it’s by demonstrating in the small cases, in the large, that you’re making those decisions in an apolitical manner. And look, not everybody’s always going to trust that. Even when you are making the decisions that way, sometimes people will ascribe partisan motivations to you. But I think as long as you know in your heart what you’re doing is for the right reasons, that you just have to keep your head down and keep going.

Joe: Given that answer, given what we’ve witnessed in recent American history here with an overt effort to, I would argue, politicize the justice department, to make it more explicit that in fact the attorney general works for the president and is an executive branch employee and serves at the pleasure of the president. What consequence does that have on our judicial and politically when it comes to our department of justice?

Sally Yates: There’s nothing that could be more corrosive, I think, to the Department. And again, going back to the issue of trust, and it’s beyond just the compounds of that particular case. I think when we witnessed an attempt to politicize the department to use it as a weapon, I think that planted the seeds of doubt about all decisions that are made, not just those decisions, not just the high profile ones coming out of main Justice, but the routine cases coming out of US attorney’s offices. And I will tell you, I saw [“was” maybe?] obviously witness to the efforts from the White House, the career men and women of the Department of Justice though, that were there during the Obama administration and there during the Trump administration. I think they were really trying to do their jobs and really trying to call the balls and strikes as they are, but they’re doing it under enormous pressure, both from within the department sometimes and from the White House. And the lingering effects of that still exist.

And so, when FBI agents go knock on someone’s door as a witness to try to get information, when jurors are called in for trials and the government is putting on its case, you can’t help but expect that some of that is in the back of their minds. That this is not really on the up and up, that there’s a different set of rules depending on who you are. And look, we’ve been struggling as a country to live up to our promise of equal justice from the time of our founding, this, I think, set us back and it’s going to take some work to get that trust back again.

Joe: Sally, I started off as a prosecutor for just about two, two and a half years as a line prosecutor and a local state office here in Massachusetts, which means you just get thrown case after case after case. I remember reading a police report once for the first time as I was in the middle of a trial asking the police officer what happened next, because I hadn’t gotten to that part in a police report yet, which is an interesting experience, right? But one of the lessons that just hit you very clearly early on from both my superiors in that office and the judges was credibility takes a lifetime to earn, and you can lose it in a second. And that there was no single case that was worth ruining your reputation over because you could never get it back, which meant on any other successive case, your judgment was going to be questioned.

And it struck me just how hard that was to earn and how fragile it was and how on every single appearance before a judge and certainly before a jury, you had to know how to navigate that. And it was a thing that you had to guard as, here in Massachusetts, as a Commonwealth attorney, you had to guard religiously, and I can only imagine that same weight obviously being able to step in a courtroom and represent the United States of America and what that must mean.

Sally Yates: It is but it’s the same obligation, whether you’re a local prosecutor in Massachusetts or a federal prosecutor in Atlanta, the same obligation. One of the things I used to talk about with AUSA is to try to crystallize it for them when I was US attorney is that to remind them that … and I know this all sounds sort of hokey, but I believe it to my core that their responsibility was not to win the case. It was not to send somebody to prison. Their responsibility was to seek justice and that’s it. And if you see that as your sole responsibility, then it makes when you’re talking about those decisions you have to make about credibility. Do you get even close to the line? The answer to that is no in all of those, because that’s inconsistent with that obligation. And that’s not to say there aren’t hard calls to make because there absolutely are. But if you can keep that one obligation in mind, it helps to clarify, I think.

Joe: So I couldn’t agree with you more. But I think that puts this next chapter for you, obviously in even greater detail.

So, if you take us back to early 2017, a Trump administration is now transitioning into office. You were at that point, I think the Acting Attorney General for the United States, after again, nearly 30 year career in the Justice Department. As President Trump was taking office, you were then thrust into multiple crises in rapid succession in the span of days. And so obviously one that I think is well known is whether to notify a brand new administration about a compromised National Security Advisor and potentially jeopardize, if you notify the White House, potentially jeopardize a major intelligence and federal law enforcement investigation with regards to Russian interference in the election.

And in that you chose to notify the White House, right? To make that choice as to balance that investigation and to do that with precautions, but you had to make a choice and you chose to notify the White House.

Shortly thereafter, you were then confronted with a decision as to whether or not to support a White House immigration policy that was politically referred to as a “Muslim ban”. And you chose [“said” maybe?] publicly that you were not going to defend that policy. That’s a heck of a first couple of weeks for new administration. Walk us through that because I can’t imagine that those choices while perhaps maybe they were clear, I can’t imagine they were easy.

Sally Yates: No. It was an action packed 10 days. That’s for sure. Not what I was expecting, but with respect to the Mike Flynn situation, that was a tricky situation in part because we did have, and the FBI had an investigation going on, on that matter. And normally what you’re trying to do and what I was trying to do there was to balance the impact it might have on the FBI’s investigation, but also with what I felt like was the Trump Administration’s right to know that they had a National Security Advisor who was potentially compromised with the Russians and a Vice President who was going out and saying things to the American people that were demonstrably false. And I felt we should give him the benefit of the doubt that he didn’t know that those things were false.

And so, there was much back and forth in the days preceding the time that I notified the White House, but it reached a point where I felt like the equities that the FBI had enough time to do what it needed to do at that point. And that the equities weighed in favor of notifying the Trump Administration. And in large part, because I felt like my responsibility in this interim time when I was acting during the Trump administration was to treat that administration the same way that I would have if it were the Obama administration.

So, I thought about, all right, let’s assume this is the Obama Administration and we got information about an official there, would we want to notify the president? Would we want to notify the White House? The answer to that was yes. And so, I felt like we should not disadvantage the Trump Administration, that our responsibilities to them were the same. So, we tried to balance it out with the impact it would have on the investigation as well from a timing standpoint, but made the decision to go forward and notify, which in the first days is a tricky scenario, to say the least.

Joe: I imagine it’s tricky no matter when. But I would also imagine that that’s, for a White House counsel that’s just literally settling into the office for an Administration that’s now settling into the responsibilities of Commander-in-Chief, obviously to be confronted with one of your top political aides, one of your top campaign surrogates being compromised by the Russians is less than ideal, I guess, to put it mildly.

Sally Yates: Yeah. But I felt like they needed the information so that they can act on it. It would be wrong of us to have this and not share it with them when they needed, in our view, to take action. But they couldn’t do that if they didn’t have the information.

Joe: And so, run us [“through” maybe] a couple of days later where you, I think leave Washington. You’re down at a dinner, you get notified of a new immigration policy that you were with senior White House officials with earlier that day, no one told you about. It ends up being controversial, to say the least. I would argue obviously illegal. You came to a conclusion that, I’ll let you walk us through it. But you also have a new administration that campaigned on a hard line on immigration and a notoriously hard line anti-immigrant former United States senator, now Attorney General, or designee at that point, hadn’t been confirmed. So, walk us through those challenges and why you decided that you couldn’t defend it?

Sally Yates: Yeah. You’re right about the timing. It was, I’d had a couple of visits at the White House on the Mike Flynn situation. And we at DOJ learned about this travel ban from reading about it in the media, which it would be hard for me to overstate right now how outside normal process that is, particularly because it falls to the Department of Justice to immediately defend when individuals are coming into the country. And I know this feels like a lifetime ago in a lot of ways. This was travel ban one. They ultimately, there were three in the administration. This is travel ban one that actually applied to people who had valid visas and were lawful permanent residents, valid green cards in the United States. And folks were literally mid-flight returning to the United States when the president signed this. And so there were lawyers all over the country, DOJ lawyers who had to respond to challenges when they were then filed when folks landed and couldn’t get into the country.

And so, as you might imagine, we spent the weekend trying to figure out what the heck this thing was, who was in, who was out, what they were trying to accomplish. There hadn’t been a lot of dialogue here. And this was over the course of the weekend. And then Monday morning, we were notified by one of the judges that she wanted us to tell her what is the Department of Justice position on the constitutionality of the travel ban? So, there was no maneuvering here or to try to deal with it on procedural issues. This is flat, DOJ, what’s your position on the constitutionality? And look, we’ve been reading all the challenges and the cases, and none of this is following like the normal process where usually 10 layers below me would do pretty memos, and they’d analyze everything and it would come up.

I’m on my iPad on LexisNexis doing research trying to read cases. And so we gathered everybody together, and that includes all the Trump appointees that had responsibility for this, as well as the career people, the one advisor that I could keep during this carry over time. And we started talking through, again, as we have been over the weekend, what are the challenges? What are the defenses? Because certainly the normal thing for DOJ is if there is a reasonable argument that can be made to defend executive action, the Department will do that. But what became really clear to me in this discussion is that to defend the travel ban, I was going to have to send DOJ lawyers into court to argue that this travel ban that applied only to Muslim majority countries, that essentially had an exception that favored Christians, that followed numerous declarations from the president of his intent to effectuate a Muslim ban, that this travel ban had absolutely nothing to do with religion. That was all for national security, nothing to do with religion.

And that was a pretext in my view. It simply was not the truth. And I don’t think any lawyer should argue a pretext, but I sure don’t think that DOJ lawyers should be doing that, not the Department of Justice. And so, at that point, it was really clear to me I wasn’t going to be part of this, the harder issue. And they’re folks who disagree with me in the position that I took on this, and I respect that, is do you resign in this or do you direct the department not to defend the travel ban? And look, if I had been the head of the Civil Division or some other component of DOJ, maybe it would have been satisfactory just to reside. But I was the Acting Attorney General. I was responsible for the entire department, and the integrity of the department and the individual lawyers that were there.

And so it seemed to me like resigning, that protects my personal integrity, but it wasn’t doing my job as the Acting Attorney General. And the risk of telling you way too long a story here, I will tell you, it was somewhat ironic that there were senators during my confirmation hearing who were all over me about whether I would say no to the president. The president they were talking about then was President Obama and it was his immigration executive orders. But I’ll remember particularly Jeff Sessions telling me, if he asked you to do something that’s unlawful or unconstitutional, or even that would bring dishonor to the Department of Justice, will you say no? And they didn’t say, will you resign? They said, will you say no? And I think they were right about that in terms of what my responsibility was. And so that’s why I directed the department to defend it.

Joe: So, you did what you said you would do, and which is what they were insinuating you should do, yet you were criticized for it.

Sally Yates: Right. I mean, it was a different president, but it seems to me the principal should be the same, regardless of which one it is. And look, they ultimately abandoned the travel ban one. They took out those provisions. So, I think ultimately, they recognized that it wasn’t lawful or constitutional either, but they just kept bagging until they could get one that could pass constitutional muster.

Joe: You mentioned a word repeatedly in that last answer, integrity. What does that word mean to you? And particularly from the perspective one, of a lawyer, two, as an attorney general of the United States?

Sally Yates: I think I felt like in a lot of ways the responsibility to act with integrity applies equally when I was a line Assistant United States Attorney as it did when I was the Acting Attorney General. I obviously had different functions then, but the responsibility to be a public servant and to be making decisions based on the fact that you represent the people of the United States is the same. And I guess maybe sort of boiling it down to its essence for me, it’s trying to make right decisions for the right reasons, recognizing that you may not always get it right. That it could be that it’s possible a different decision in retrospect would have been the better one. But trying really hard to be guided by a compass that’s pointed in the right direction, to take that responsibility to represent the people of the United States, and the principles, and the laws and the Constitution seriously, and to make the best decision that you can guided by those principles.

And then to own it, to be willing to accept the consequences of it as well. And to me, it’s a responsibility that, my gosh, what a privilege it is too. I feel like the luckiest person in the world to have had a chance to spend 27 years at the Department of Justice and all the positions that I had, and certainly to be able to in my career as deputy attorney general and ever so briefly as acting attorney general, how lucky am I in that?

Joe: Sally, I’ve had the opportunity to talk to obviously former colleagues and others that are aspiring for office. And the point that I try to come back to in that is that all of those positions, essentially, we are renting. They existed before you, and they’re going to exist after you, and you are privileged enough to hold it for a moment in time. And what you want, ideally from my perspective, to be able to say, is that your service there mattered and that you made a contribution with it. And I think, at least taking from me, your service there mattered and you made a huge contribution to it in standing up to that principle at a time when it was the weight of the world literally on your shoulders. And you didn’t have to, but we are grateful that you did. Thank you.

Sally Yates: It was a privilege.

This interview has been slightly edited and condensed for clarity. To watch the full version, click here. It was featured in the April 11, 2021 edition of The Sunday Paper. The Sunday Paper publishes News and Views that Rise Above the Noise and Inspires Hearts and Minds. To get The Sunday Paper delivered to your inbox each Sunday morning for free, click here to subscribe.