The Sunday Paper Recommend: NatGeo Interview with Jane Goodall

When she was a child in England reading Doctor Doolittle books, Jane Goodall imagined living in Africa, studying its animals. In her early 20s, she traveled to Kenya, where she so impressed paleontologist Louis Leakey that he hired her to conduct chimpanzee research; she began fieldwork in 1960 at the Gombe Stream Game Reserve in what’s now Tanzania. Goodall observed never-before-seen behaviors, such as toolmaking and tool use by chimps, including a white-whiskered one she called David Greybeard. Her discoveries revolutionized primate science, prompting the National Geographic Society to fund her work and commission Hugo van Lawick (who would become Goodall’s first husband) to capture it on film. Television, magazine articles, and books made Goodall a household name. Her acclaimed work through the Jane Goodall Institute includes establishing chimp sanctuaries and promoting conservation. Now 85, she starred in Brett Morgen’s 2017 documentary Jane, which depicted her life and work.

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC: What is your greatest strength?

JANE GOODALL: I would have to say being determined, open-minded, optimistic; having an innate ability to communicate, and a good constitution (which is genetic!)—but I’ll leave it up to you to decide.

NG: Have you had what you’d call a breakthrough moment in your life?

JG: I’ve had many breakthrough moments. One was seeing the chimpanzee I called David Greybeard using and making tools. That resulted in Louis Leakey approaching the National Geographic Society, which then agreed to fund the research. Another breakthrough moment was David Greybeard taking a palm nut from my outstretched hand, dropping it, but then gently squeezing my fingers—that’s how chimpanzees commonly reassure each other. We communicated, perfectly. At that moment I knew I was committed to understanding and protecting chimpanzees for my life.

There was the realization in 1986 that chimpanzee numbers across Africa were declining due to loss of habitat, bushmeat trade, and human population growth. And then, in 1990, flying over Gombe and seeing a tiny 35 square kilometers of forest surrounded by completely bare hills. The villagers living around Gombe had been struggling to survive and began cutting down trees to try to grow food for family. This caused terrible soil erosion and poverty, and it hit me that unless we helped the people to find alternative ways of living and improved their lives, there was no way we could even try to save the chimpanzees. This led to the birth of the TACARE project, or Take Care: helping people first of all in the ways that they suggested, not that we imposed, such as restoring fertility to the overused farmland without chemicals, helping them grow more food.

Finally, there was the embrace I received from our Tchimpounga sanctuary chimpanzee Wounda when she was released onto her new island sanctuary in the Republic of Congo. She had been rescued from the illegal bushmeat trade and received the first chimp-to-chimp blood transfusion in Africa. The embrace lasted almost a minute; it was the most moving thing that has ever happened to me, and it made all of the hard work worthwhile. I met her for the first time that day. It was as though she knew who began it all, said one of the Congolese caretakers.

NG: What is the most important challenge facing women today?

JG: In so many developing countries, women have no freedom, no chance (unless they are exceptional) of developing their own careers. In poor communities, families tend to provide money to educate boys over girls. Some girls are forced to stop going to school at puberty as there is no privacy, or hygienic lavatories, or provision of sanitary supplies. There are still cultures where menstruating girls must stay alone in a hut until their period is over. In Saudi Arabia, women weren’t even allowed to drive until just very recently. In many cultures women have no access to family planning, have numerous children and are solely responsible for their care and upbringing, as well as having to do the chores and cooking single-handed (until helped in some cultures by a second, then third wife). For these reasons not only women but children—and thus our future—will suffer.

NG: What living person do you most admire?

JG: There are many people living today I admire greatly. Iain Douglas Hamilton represents those scientists who have devoted their entire lives to conservation; in his case it is the elephants. Vandana Shiva, who fights to protect forests and women’s rights in India—and, again, she represents so many people who devote their lives to protecting the environment. Muhammad Yunus, who brought hope to millions of women through the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, a microfinance organization and community development bank that makes small loans to help lift people from poverty. Then there’s Mikhail Gorbachev, the former leader of the Soviet Union who helped to end the Cold War. And Gary Haun, who went blind at 21 in the U.S. Marines and decided to become, of all things, a magician. He does shows for children and they don’t know he’s blind, and then he’ll say, “Things may go wrong in your life, but even if they do, don’t give up.” He now does scuba diving, skydiving, cross- country skiing, and has taught himself to paint! Almost 25 years ago, he presented me with my mascot, a stuffed monkey (which he thought was a chimpanzee) named Mr. H.

NG: Which historical figure do you most identify with?

JG: Charles Darwin, who was fascinated by wildlife from childhood. In the Galápagos Islands, he worked out a theory of evolution. His suggestion shocked mainstream academia and religion; the suggestion that we are descended from apelike ancestors was heresy. In the same way, when I attributed personality, mind, and emotions to chimpanzees, mainstream science was horrified: Only humans share these characteristics, they said. Darwin did not abandon his theory, despite the criticism. Nor did I.

NG: Where are you are most at peace?

JG: Out in nature by myself.

NG: What advice would you give to young women today?

JG: The advice my mother gave to me, which is, “If you really want to do something you will have to work hard, take advantage of opportunities, and never give up.” Also, that you may not achieve your dream immediately, but keep it alive and seize any opportunity to make it reality.

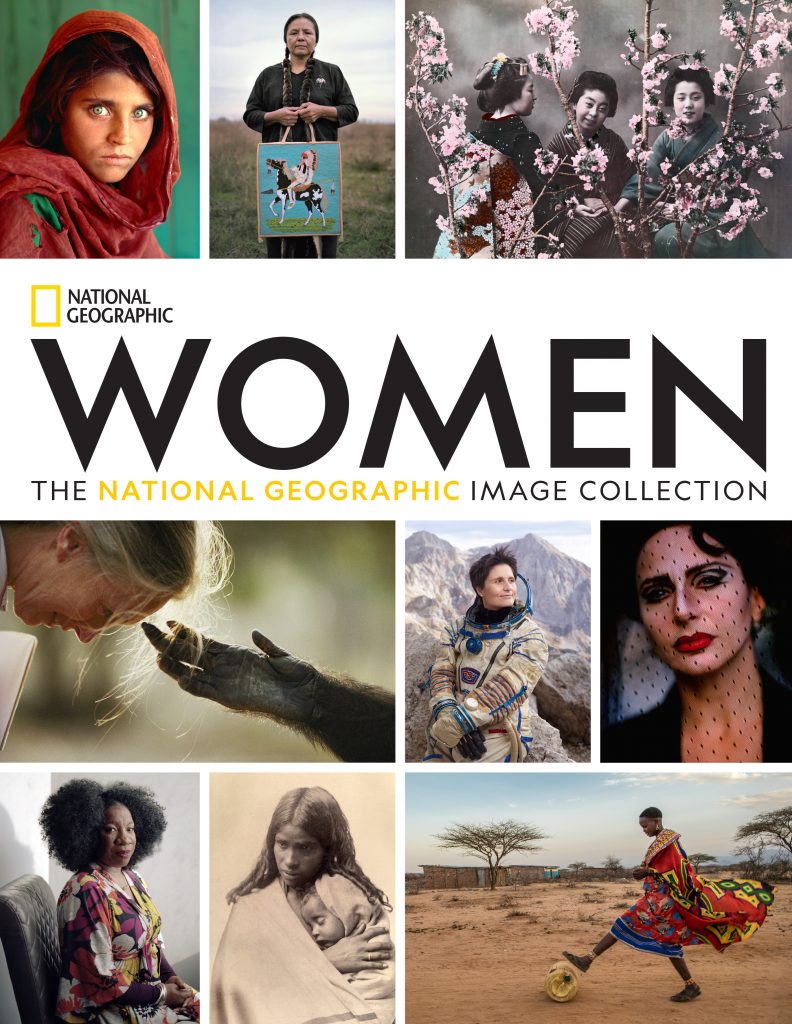

Image and adapted excerpt provided for one-time use for coverage or promotion of WOMEN: THE NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC IMAGE COLLECTION. Copying, sublicensing, sale, distribution and archiving are prohibited.