What to Make of the Widow…

It was a revelation. The word suddenly felt different. I may not have looked like a widow, but I felt like one. Widow once described a much older woman. Old, wrinkled, tragic. Wearing black. Maybe even a veil. I felt like a version of Charles Dickens’s jilted old Miss Havisham, but instead of being left at the altar and staying in my wedding dress forever, I was left in midlife, barefoot in shiva clothes and a blowout.

Once I started referring to myself as a widow, I couldn’t stop. I don’t know what took me so long to claim it. That’s what it felt like; that I was claiming the word, asserting some truth about myself because it wasn’t obvious if you looked at me. And in saying it, declaring it, embracing it, I was convincing myself that it was real. Joel was gone. He was still my husband. We were still married, but I was a widow.

A widow.

I’d be at the car wash, and while waiting for our cars, the person next to me might say something like, Last time I got a car wash, it rained the next day.

I’d reply, Oh, I hate it when that happens. Especially because I’m a widow.

Or, Sophie and I would be at the In-N-Out Burger drive-through. I’d give our order through the speaker. We’ll take one double-double, two large fries, and two chocolate shakes . . . because I’m a widow.

Sophie would roll her eyes, mortified. “M-o-o-o-m!”

“Maybe they’ll throw in something free!” I’d say to her as we drove to the pay window. “Some sympathy fries or something.” They never did.

Once when I took the dogs to the groomers, and they said they’d be ready at three o’clock, I replied, “No problem. I’m a widow; I’ll be here at three!”

The word didn’t scare me. It didn’t make me cower. It gave me something to say, a way to place myself in the world. I had a word for what I was, and I used it. It felt powerful.

When I dropped the word, and the stranger realized that I said widow, I would see the wheels in their mind spinning, waiting to register. Once it did, they would stare at me, stunned, confused. I never would have guessed! someone once said. Maybe that’s why I felt compelled to tell people, to say it out loud. Saying I was a widow made it real. For me, it was impossible to understand that my husband died. It made no sense. We were supposed to grow old together. We shared a life. We loved and liked each other. It’s not that I wanted people to know, I needed them to.

Everyone in my neighborhood, of course, already knew. Some decided I was in need of not just their condolences but their sympathy. I was once at Trader Joe’s trying to figure out what to make with the chicken I had just put in my cart when a woman I knew from the neighborhood came up to me crying, tears pouring down her face.

“Melissa.” She sniffed. “How are you?” She tried to pull me into a hug, but thankfully my shopping cart was in between us. She settled by putting her hands on my arms.

“I’m so sorry. I keep thinking of you and Sophie, and I just keep crying.”

This woman was never my favorite. Years ago she had a birthday party for her kindergartner and invited everyone in the entire class. Everyone but Sophie. I’m sure it was an oversight, but I never got over it. So when she came to me crying, I offered no words of comfort (because, hello, I’m the one who is grieving) and I didn’t feel the need to fill up the space. I preferred it being awkward. I watched her face get red, the tears pouring down. She continued to cry, and then the truth of her being upset really came out.

“I just . . . ,” she said with a sob. “I don’t know what I would do if it were me.”

There. She said it. Her tears, her crying, her sympathy had nothing to do with me. It had to do with her. Her fears. Her own anxiety over the possibility, however slim, of losing her husband. Having her world rocked upside down. I looked at her with indifference.

“Feel better,” I said as I wheeled my cart away.

I could own the fact that I was now the town widow, but what I couldn’t take was everyone’s projections and assumptions. People knew about me, so they thought they knew me, thought they knew my story.

They didn’t.

They didn’t know my suffering or Joel’s. They didn’t know that I felt like I was grieving long before Joel had even died. That I was grieving before I even knew I was grieving.

It’s common for widows to feel like they are the ones who need to comfort those who are trying to comfort them. I wish I could offer suggestions of the appropriate things to say, but the truth is, I don’t know. Grief is personal and private.

For me, I just wanted the acknowledgement (I’m so sorry would usually suffice), and depending on the person, I didn’t necessarily want much else. I didn’t want to make small talk or hear about their eighty-five-year-old aunt who just died in their weak attempt to make their situation relatable to mine.

Nor did I want a hug.

Some people got it just right. Like the time I was doing Clooney, and I saw a woman from the neighborhood who hikes there daily. We aren’t friends, but we’ve known each other for years. She saw me crying, sniffling, working my way up the hill. She was coming toward me in the opposite direction. I didn’t want to stop, but I saw her sigh when she saw me. She simply reached out and squeezed my arm as we passed each other. There was no pretense. No over-the-top outburst. My situation was sad. Unbelievable. Hard to fathom . . . and her simple, silent acknowledgement was enough.

Or the friend I ran into from my early days of working at Atlantic with Joel. I barely recognized her; it had been so many years. But she stopped me and said, “I heard about Joel. I’m so sorry.” And then continued reminiscing about the old days. I appreciated that she saw my circumstance as a matter of fact. She didn’t exude any pity or projections of her own.

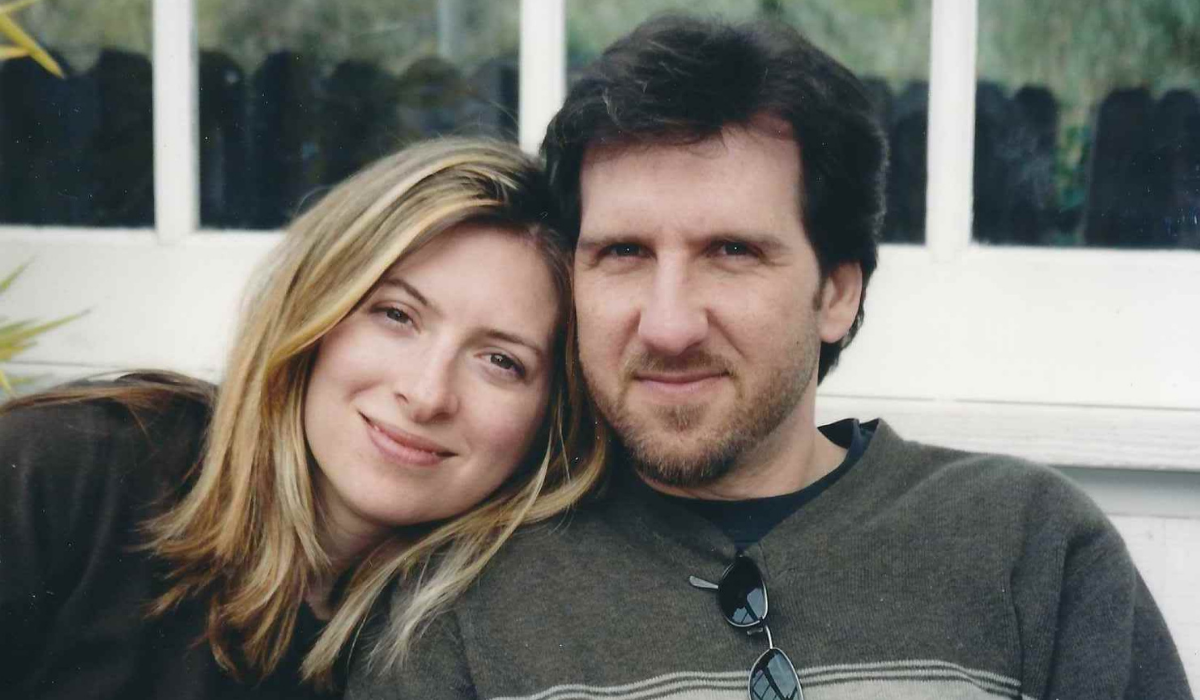

People knew Joel and me as a happy couple. They knew us as Sophie’s parents. They knew that we lived in the house close to the elementary school (which at one point or another, everyone with kids in our neighborhood had parked in front of). But now I was the woman whose husband had died. The husband who everyone saw riding through the neighborhood on his bike. The husband who was so nice. What did he have again? What was wrong with him? How did he die?

And if that could happen to me, couldn’t it happen to anyone? How will she manage? In that big house, just her and her daughter? Oh my God! What’s she going to do now?

No one knew what to make of The Widow. The truth is, I didn’t know either.

Excerpted from Widowish with permission from the author.